Part 2: From Query Patterns to Intelligent Tools & Agent Design

A simple search application can take in keywords, find exact matches and return results. It cannot however, reliably and accurately decipher natural language queries which involve semantic understanding of the users' intent. The benefit of using an agentic search application is that the AI Agent has the power to decipher the user queries fully, breaking them down into multiple parts (“Which talks from 2024 discuss LLM deployment in prod?” → filter: 2024, semantic search: LLM deployment in prod) and using one (or more) of the tools at its disposal to fetch relevant data, reason over it and answer the query. Therefore, it’s also understandable that an AI agent is only as good as the tools it wields. Part 1 of this series established the data foundation: a graph schema designed for LLM query decomposition, multimodal embeddings connected to source entities, and query patterns that translate natural language into database operations. That foundation was built with a specific goal - enabling an AI agent to autonomously navigate complex user queries about MLOps conference content, which is fairly representative of how users tend to have a collection of mix modalities for their usual search use cases.

This post completes the journey. The query patterns tested in Part 1 now become parameterized tools, and a ReAct agent learns to select and compose them based on user intent. The focus here is on tool design philosophy, the consolidation of dozens of query patterns into seven comprehensive tools, and the few-shot prompt engineering that teaches the agent effective tool usage. The full application code, including the FastAPI backend and Next.js frontend, is available in the GitHub repository. You can yourself try out the agent as well and share feedback with us.

Dataset: MLOPs Conference Talks from 2022-2024 (.csv)

Embedding model: EmbeddingGemma by Google

Frameworks: Python FastAPI for backend, Next.js for frontend

Platform: Netlify for frontend deployment, Render for backend deployment

Metadata, text and vector storage: ApertureDB

Event agent: try out the agent

GitHub Repository: Repo

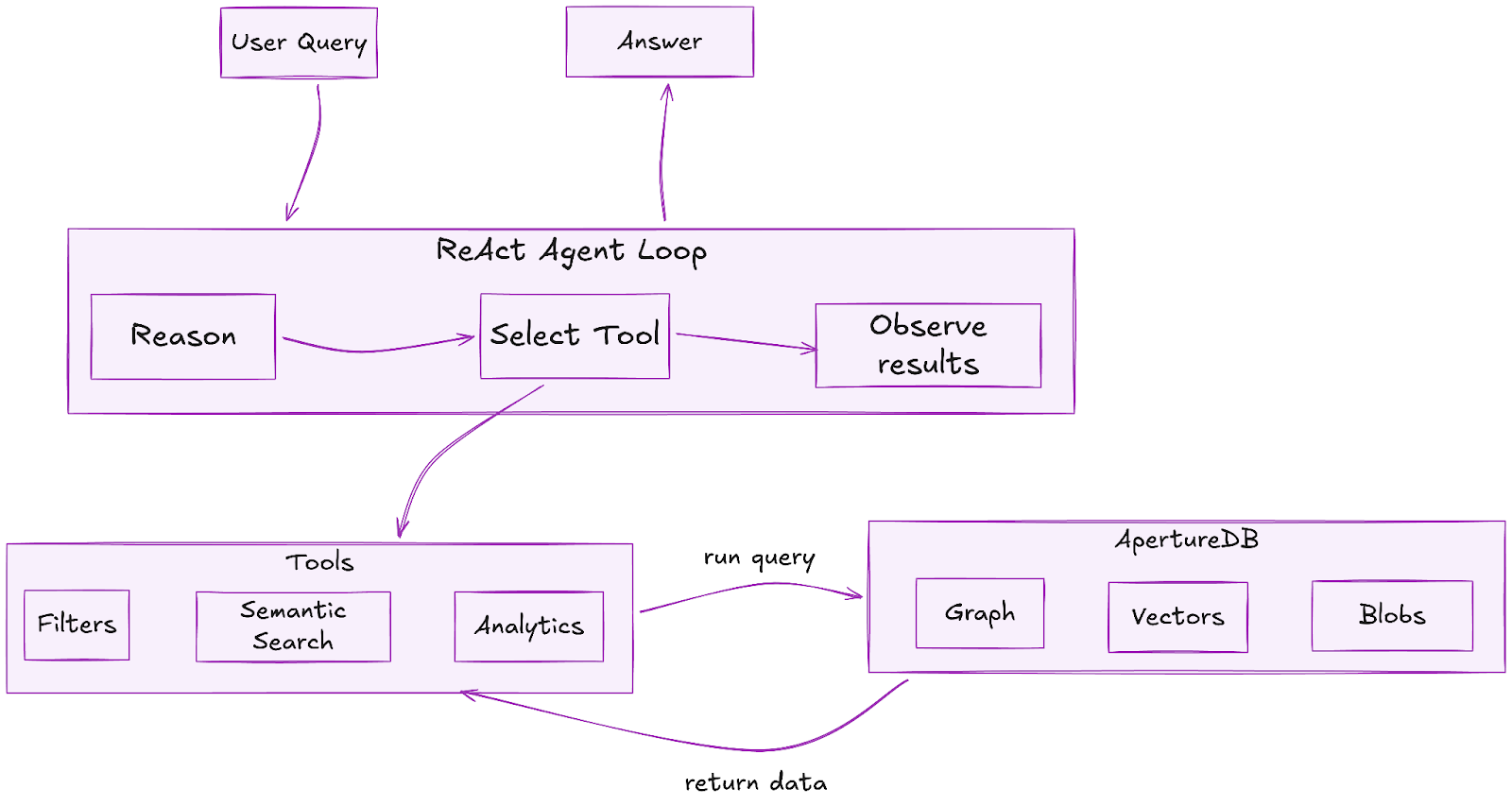

The Application Flow

The diagram shows the execution flow of the agentic application. The user prompts the AI agent with a natural language query. The AI agent then iterates in a ReAct (reasoning + action) loop which involves reasoning or “thinking” about an action to take i.e deciding which tool best matches the query requirements and hence should be used, as well as which params the tool should be called with. Once the agent has reached a decision, it calls one or more tools (multiple tools can be called in parallel thanks to LangGraph), the tools execute ApertureDB queries under the hood, parse the raw result to strip away unnecessary details and information (like raw ApertureDB logs etc) and then return back to the AI agent. The AI agent uses the retrieved results to decide the next course of action - either calling a tool again or generating the final answer. The last tool call’s top 10 retrieved results (if they contain Talk items) are also returned and displayed in the UI for the user to navigate directly. An important thing to mention here is the importance of sanitizing the returned DB results so you only provide back to the LLM the necessary information rather than overloading its context window with unnecessary material. This type of context engineering requires a lot of nuance and curation but it heavily affects the quality of agentic applications.

The Philosophy of Tool Design

The critical insight that has shaped this implementation is that tool design matters more than model selection. A powerful LLM with poorly designed tools produces unreliable results; a well-designed toolset enables even modest models to deliver consistent, high-quality outputs. Following best practices in context engineering for AI Agents outlined by Anthropic, LangChain and Manus, we followed these five design principles during our tool development process.

First, tools must be self-contained. Each tool handles a complete workflow - query construction, database execution, result formatting - without requiring the agent to coordinate multiple steps. This dramatically reduces the reasoning burden on the LLM and minimizes failure modes.

Second, tools must be parameterized. Rather than creating separate tools for "filter by date" and "filter by views," a single tool accepts multiple optional parameters that the agent can combine as needed. Pydantic schemas provide both type validation and documentation that the LLM reads to understand parameter usage.

Third, tools must be well-documented. The docstrings serve dual purposes: they explain functionality to developers and provide instructions to the LLM during tool selection. Comprehensive descriptions of when to use each tool and what each parameter means directly improve agent accuracy.

Fourth, tools must produce structured outputs. Consistent JSON response formats reduce parsing errors and enable the agent to reason about results predictably. Every tool returns a success flag, meaningful error messages on failure, and structured data that maps cleanly to natural language responses.

Fifth, tools must degrade gracefully. Database queries can fail, speakers might not exist, searches might return no results. Each tool handles these cases explicitly, returning informative messages rather than crashing. The agent can then communicate failures naturally to users or retry another tool or the same tool with different parameters (tried and tested!).

From Query Patterns to Curated Tools

Part 1 tested dozens of ApertureDB query patterns: metadata filtering with sorting, semantic search across multiple descriptor sets, graph traversals from Person to Talk entities, constrained semantic search that filters before vector similarity, and aggregation queries for analytics. The observation that drove tool consolidation: many of these queries share common structures with variable parameters.

The filtering queries - by date, by views, by category, by speaker - all reduce to a single FindEntity operation with dynamic constraints. The semantic searches across transcripts, abstracts, and speaker bios all follow the same FindDescriptor → FindEntity pattern with different descriptor sets. During this consolidation process, we identified seven tools that cover the full query space, each handling multiple related use cases through parameterization. A few of the core tools are covered briefly in the remaining article. You can find the complete code for all the tools in the GitHub repo.

Here’s a refresher for the schema that we curated and discussed in Part 1 of the series:

- Entities:

- Talk (core): typed properties for filters (views:int, date, tech_level, company, track, keywords, abstract, outcomes, youtube_id). Deterministic UUIDs.

- Person: normalized speakers.

TranscriptChunk: timestamped 10-segment chunks for semantic search.

- Connections:

- TalkHasSpeaker (speaker lookup + multi-hop reasoning).

- TalkHasTranscriptChunk (constrained semantic search).

- TalkHasMeta (talk-level embedding link).

- Descriptor Sets:

- Transcript chunks (~17k vectors), talk metadata (~280), speaker bios (~263).

- Key design principles: typed fields for agent filters, graph modeling for traversal logic, chunk embeddings for precise semantic search, deterministic ingestion for reproducibility.

Our database schema curation + query testing laid the foundations for these comprehensive tools. ApertureDB’s well-curated and versatile query language is what enabled the easy schema curation to begin with.

Tool 1: search_talks_by_filters is heavily metadata-based, handling all queries that don't require semantic understanding. The Pydantic schema illustrates how parameters become self-documenting:

class SearchTalksByFiltersInput(BaseModel):

date_from: Optional[str] = Field(

None,

description="Filter talks published from this date (format: YYYY-MM-DD, YYYY-MM, or YYYY)"

)

min_views: Optional[int] = Field(

None,

description="Minimum YouTube view count required. Example: 1000 for talks with at least 1K views"

)

company_name: Optional[str] = Field(

None,

description="Filter by speaker's company name. Example: 'Google', 'Microsoft', 'OpenAI'"

)

sort_by: Optional[Literal["date", "views", "title", "tech_level"]] = Field(

"date",

description="Sort results by: 'date', 'views', 'title', 'tech_level'"

)

limit: Optional[int] = Field(10, description="Maximum number of results to return")The description fields are read by the LLM during tool selection - they're not just documentation, they're instructions. When a user asks "Show me talks from Google with over 1000 views," the agent reads these descriptions and constructs the appropriate parameter combination. The tool internally builds ApertureDB constraints dynamically based on which parameters are provided.

Tool 2: search_talks_semantically handles natural language queries by searching across multiple embedding spaces. The key design decision: search all three descriptor sets (transcripts, abstracts, speaker bios) and merge results ranked by similarity. This ensures comprehensive coverage regardless of where relevant content appears.

sets_to_search = [

(SET_TRANSCRIPT, "TalkHasTranscriptChunk", "transcript"),

(SET_META, "TalkHasMeta", "abstract/metadata"),

(SET_BIO, "TalkHasSpeakerBio", "speaker bio")

]The tool also supports constrained semantic search - a pattern that exemplifies ApertureDB's unified architecture advantage. When a user asks "Find talks about RAG from 2024," the tool first filters Talk entities by date, then searches only within those talks' connected embeddings. This happens in a single atomic query:

q = [

{"FindEntity": {

"_ref": 1, "with_class": "Talk",

"constraints": {"yt_published_at": [">=", {"_date": "2024-01-01"}]}

}},

{"FindDescriptor": {

"set": "ds_transcript_chunks_v1",

"is_connected_to": {"ref": 1, "connection_class": "TalkHasTranscriptChunk"},

"k_neighbors": 10, "distances": True

}}

]With separate vector and relational databases, this constrained search pattern requires complex orchestration - multiple round trips, application-level joins, addressing consistency challenges. ApertureDB's connected embeddings make it a single query.

Tool 3: analyze_speaker_activity leverages the graph structure established in Part 1. The separate Person entities connected via TalkHasSpeaker edges enable powerful speaker-centric analytics. For individual speaker analysis, the tool traverses from Person to all connected Talks:

q = [

{"FindEntity": {

"_ref": 1, "with_class": "Person",

"constraints": {"name": ["==", speaker_name]}

}},

{"FindEntity": {

"with_class": "Talk",

"is_connected_to": {"ref": 1, "direction": "in", "connection_class": "TalkHasSpeaker"},

"results": {"list": ["talk_title", "yt_views", "category_primary", "event_name"]}

}}

]For dataset-wide analysis, the tool aggregates all talks by speaker, calculates statistics (talk counts, total views, categories covered), and identifies repeat speakers. For users unfamiliar with the graph data model, the schema design we did in Part 1 might have seemed like an overhead but it is what efficiently supports queries that would otherwise be expensive string operations in a flat table structure (learn more about value of graphs from this blog).

Tools 4-7 complete the suite. get_talk_details provides deep-dive capability with optional transcript chunks filtered by time range and semantically similar talks. find_similar_content handles recommendations using content-based, speaker-based, or topic-based similarity. analyze_topics_and_trends extracts tool mentions, technology references, and keyword frequencies using pattern matching against curated lists. get_unique_values serves as a discovery tool, answering "What events exist?" or "What categories are available?" - essential for agents to understand the data landscape before filtering.

The Few-Shot Prompt

The system prompt spans over 500 lines and represents the accumulated wisdom from iterative testing. The agent's performance improved dramatically with detailed few-shot examples showing parameter selection and tool chaining patterns, as compared to initial tests with a simpler system prompt. The prompt structure includes four components:

- database schema explanation,

- tool descriptions with selection guidelines,

- fourteen few-shot examples, and

- response formatting guidelines.

The tool selection guidelines provide explicit mappings from query types to tools:

Filtering & Sorting → search_talks_by_filters

Topic-Based Search → search_talks_semantically

Speaker Analysis → analyze_speaker_activity

Detailed Information → get_talk_details

Recommendations → find_similar_content

Trend Analysis → analyze_topics_and_trends

Discovery → get_unique_valuesThe few-shot examples demonstrate not just which tool to use, but how to construct parameters. Consider this example for expert finding:

### Example 4: Expert Finding (Tool 2)

**User Query**: "Find experts who talk about vector databases and RAG"

**Tool Call**:

search_talks_semantically.invoke({

"query": "vector databases RAG retrieval augmented generation embeddings",

"search_type": "bio",

"limit": 8

})The example teaches the agent that searching speaker bios (search_type: "bio") is the appropriate strategy for finding experts, and that expanding the query with related terms improves recall. Without such examples, agents often make suboptimal parameter choices, searching transcripts when bios would be more relevant, or using overly narrow queries. The entire system prompt for the agent is very comprehensive and spans 280 lines. But this well-curated prompt with sufficient few-shot examples on tool usage is what makes the AI Agent’s performance so reliable and successful.

The ReAct Agent

The agent implementation uses LangChain's prebuilt LangGraph-based create_agent function with Gemini 2.5 Pro as the reasoning model. It uses the ReAct (Reasoning + Acting) pattern that fits database exploration tasks naturally: the agent thinks about what information is needed, selects and executes a tool, observes results, and reasons about whether additional tools are required.

from langgraph.prebuilt import create_react_agent

from langchain_google_genai import ChatGoogleGenerativeAI

model = ChatGoogleGenerativeAI(

model="gemini-2.5-pro",

temperature=0.7,

google_api_key=GOOGLE_API_KEY

)

tools = [

search_talks_by_filters,

search_talks_semantically,

analyze_speaker_activity,

get_talk_details,

find_similar_content,

analyze_topics_and_trends,

get_unique_values

]

agent = create_agent(model=model, tools=tools, system_prompt=system_prompt)The Agent in Action

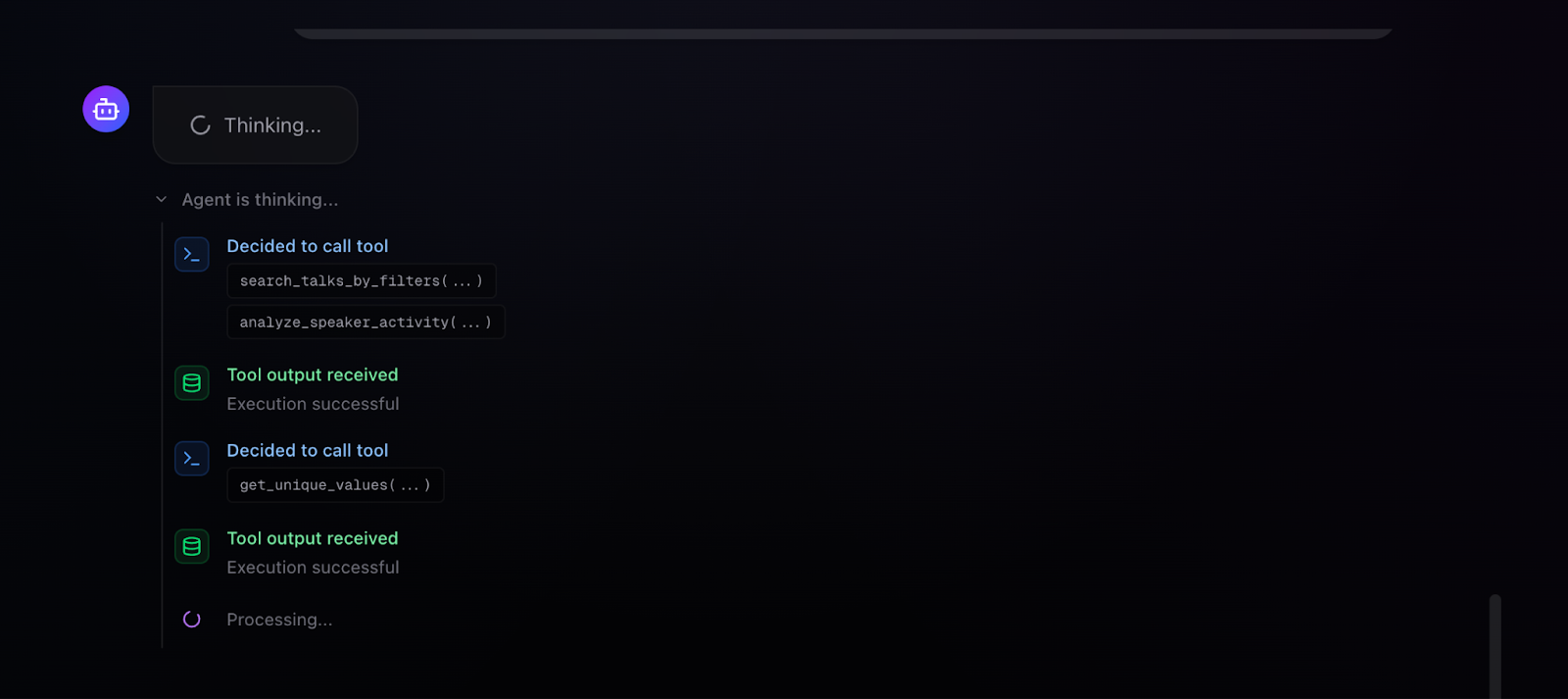

We have deployed our agent application as a FastAPI backend with Server-Sent Events (SSE) for real-time streaming, paired with a Next.js frontend that visualizes the agent's reasoning process. The screenshots demonstrate the agent handling real queries with full transparency into its decision-making.

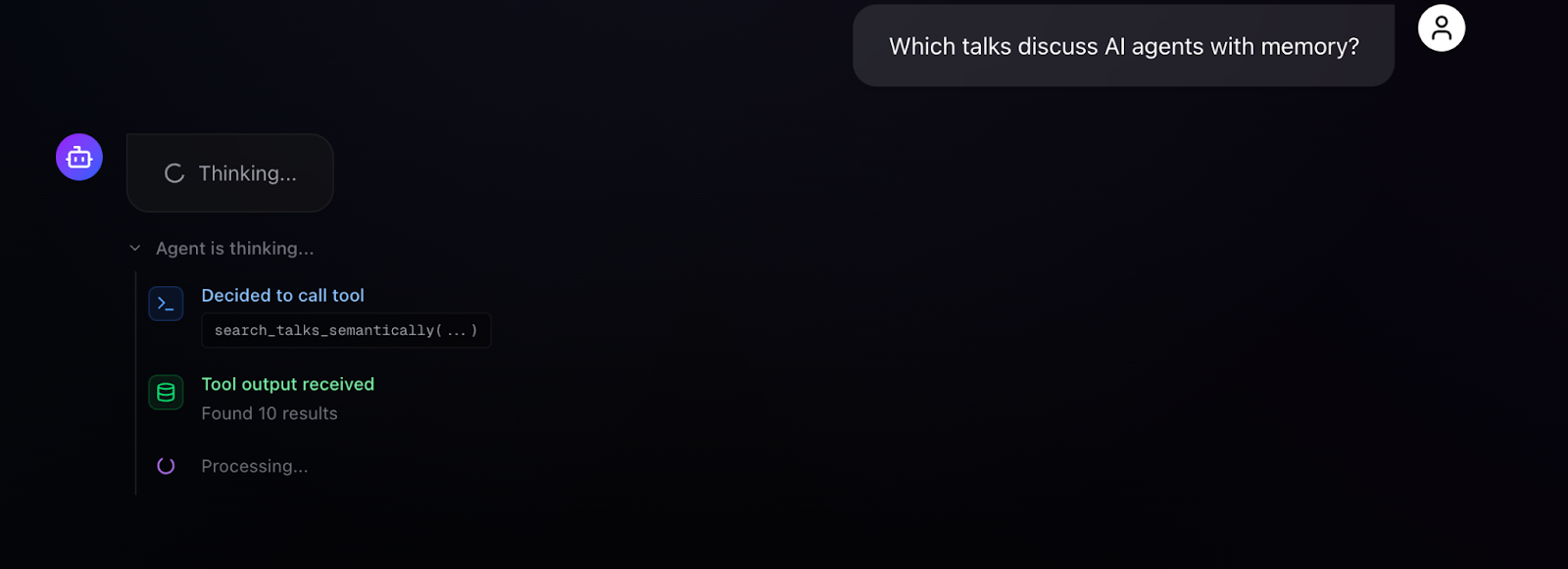

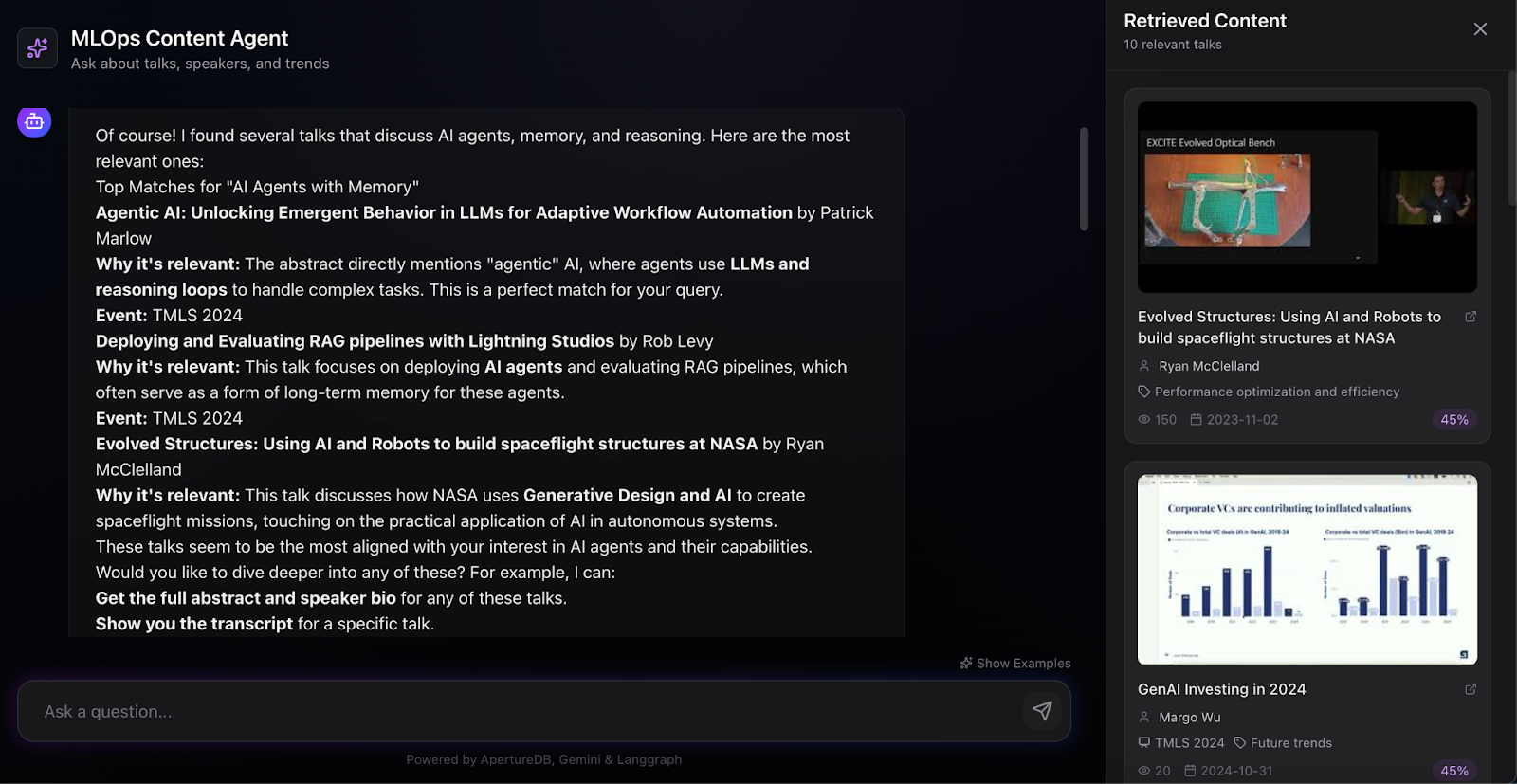

For a simple semantic search - "Which talks discuss AI agents with memory?" - the agent selects search_talks_semantically with an appropriate query, receives 10 results, and synthesizes a response explaining why each talk is relevant. The UI visualizes the chain of thought: "Agent is thinking... Decided to call the tool: search_talks_semantically(...) Tool output received: Found 10 results... Processing..." The retrieved content panel displays talk cards with thumbnails, speaker names, categories, view counts, and similarity scores, giving users both the agent's interpretation and direct access to source material.

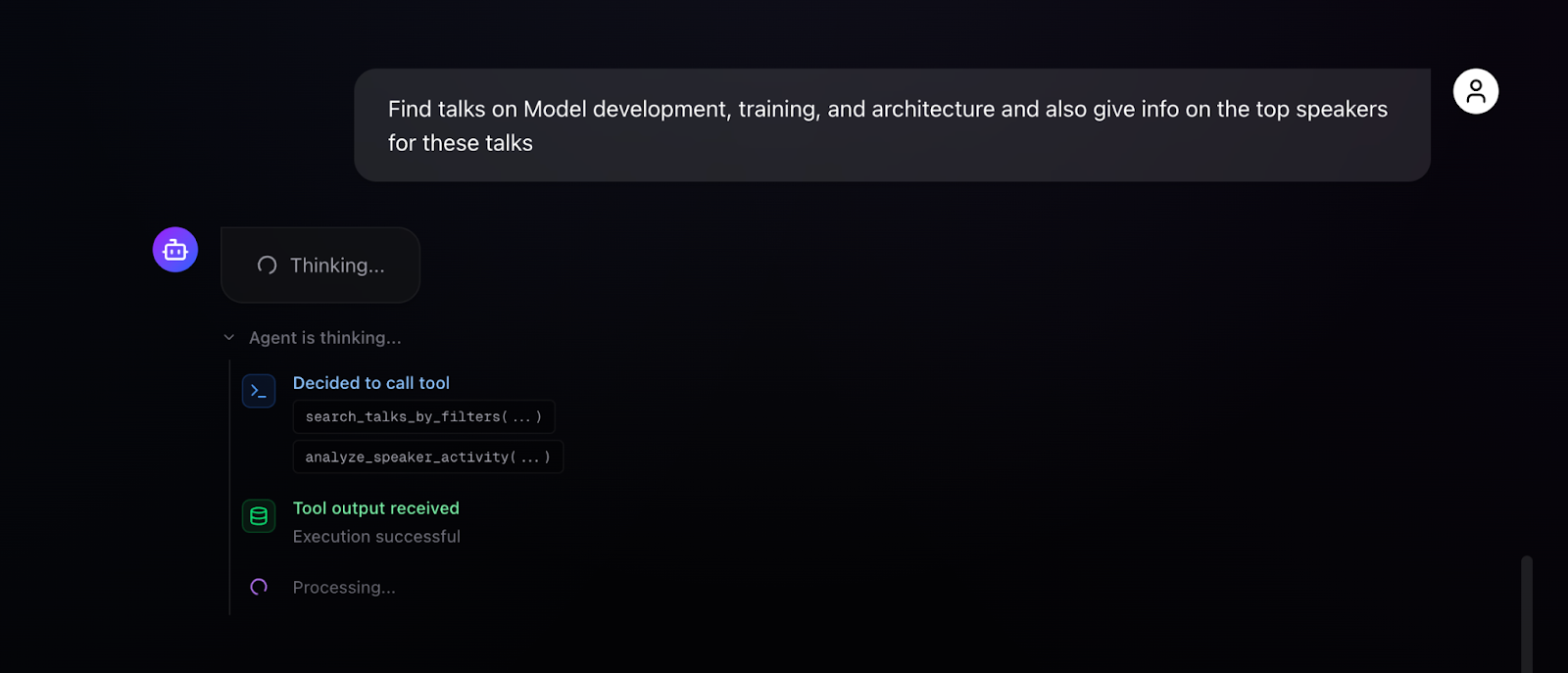

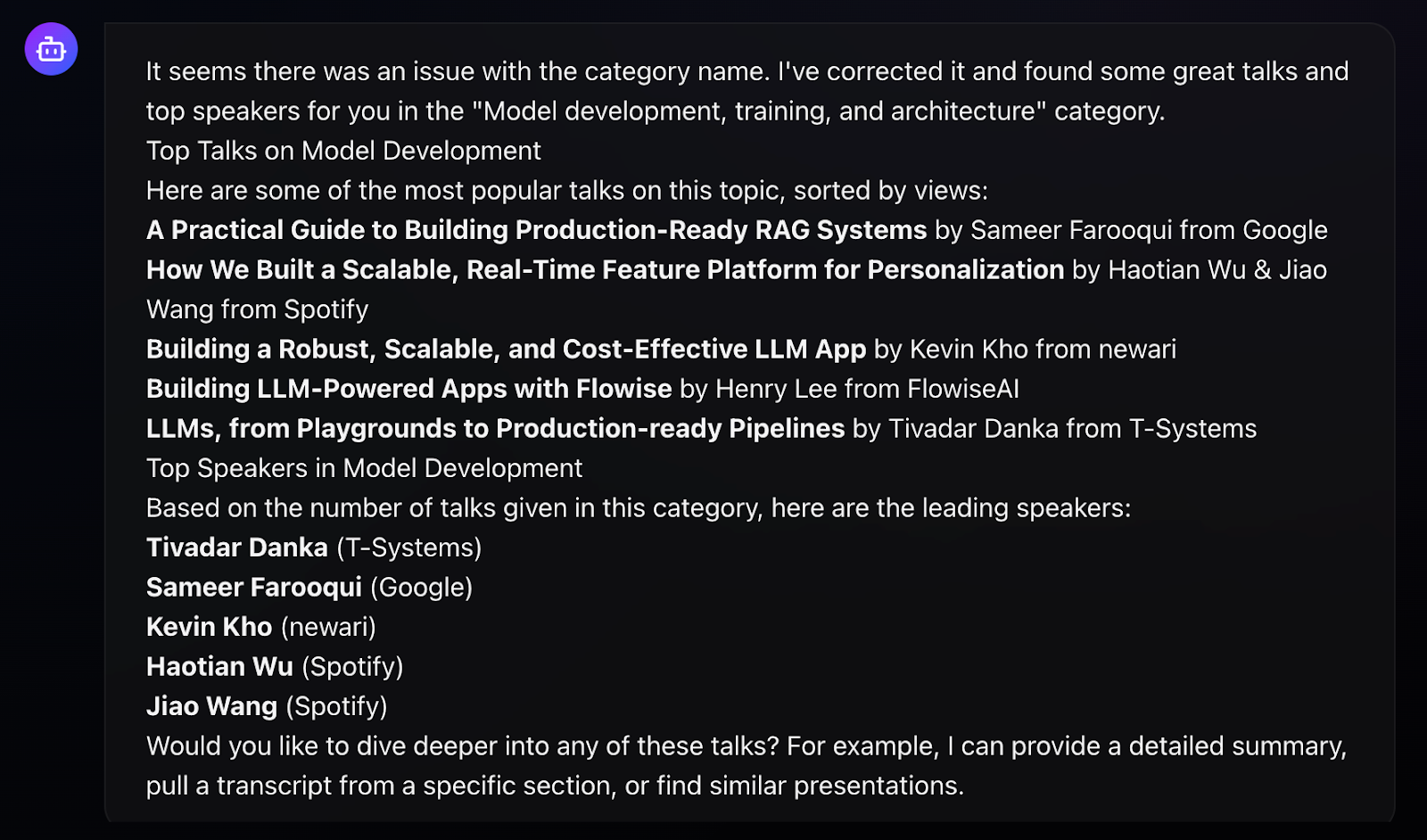

More interesting is multi-tool chaining. When asked "Find talks on Model development, training, and architecture and also give info on the top speakers for these talks," the agent autonomously executes multiple tools in sequence: search_talks_by_filters to find relevant talks, analyze_speaker_activity to analyze the speakers presenting in this domain, and get_unique_values to discover available filtering options. The execution trace shows each tool call with its parameters, the success status, and processing indicators. The final response combines talk recommendations with speaker analytics identifying top contributors.

This autonomous tool composition is the payoff from careful tool design. Because each tool is self-contained and returns structured results, the agent can chain them without confusion. Because the few-shot examples demonstrate multi-tool patterns, the agent knows this composition is possible and appropriate.

Lessons Learned

Building this agent has led to several insights that generalize beyond this specific application:

- Tool design determines agent capability more than model selection. The seven tools, with their comprehensive parameters and structured outputs, define what the agent can accomplish. Upgrading the LLM might improve response quality, but the tools define the possibility space. Time invested in tool refinement; better parameter descriptions, more informative error messages, richer structured outputs, pays dividends in agent reliability.

- ApertureDB's unified architecture eliminated an entire category of complexity. Graph traversals, vector similarity search, and metadata filtering happen in singular atomic queries. The constrained semantic search pattern - filter first, then search embeddings - otherwise requires significant orchestration with separate systems. For AI agent applications that need to combine structured queries with semantic understanding, having graph, vector, and blob storage in one transactional system is a significant advantage. The connected embeddings pattern, where each vector links back to its source entity, enables query patterns that simply aren't practical with separate databases.

- Few-shot examples are not optional. The improvement from adding detailed examples to the system prompt was substantial and immediate. Examples teach the agent not just tool selection but parameter construction, query expansion strategies, and multi-tool patterns. The fourteen examples in the system prompt cover the full range of query types users might ask - from simple filtering to compound analytical requests.

- Pydantic schemas serve as LLM documentation. The Field(description=...) annotations are read by the model during tool selection. Well-written descriptions directly improve parameter accuracy. This dual-purpose design - validation for developers, documentation for LLMs - is worth adopting broadly.

The completed system demonstrates what becomes possible when data architecture, tool design, and agent orchestration are aligned toward a common goal. The graph schema from Part 1 enables the traversals that power speaker analytics. The connected embeddings enable constrained semantic search. The parameterized tools expose these capabilities to an LLM that can reason about user intent and compose operations autonomously. Each layer builds on the previous, and the result is an intelligent search interface that handles complex, multi-faceted queries about MLOps conference content. Not only that, but a similar series of steps can easily be adopted for other

The best part, you can test the application yourself and use the steps outlined or the code to build your own. The full source code is available on GitHub. ApertureDB documentation and API reference can be found at docs.aperturedata.io.

I would like to acknowledge the valuable feedback from Sonam Gupta (Telnyx), and Vishakha Gupta, in creating this Agent and blog.

Part 1 of this series

Ayesha Imran | Website | LinkedIn | Github

Software Engineer experienced in scalable RAG and Agentic AI systems, LLMOps, backend and cloud computing. Interested and involved in AI & NLP research.

.png)

.png)

.jpeg)

.png)